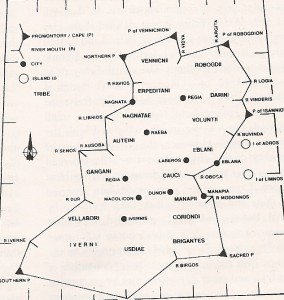

That Ireland was reasonably well known in the classical world is demonstrated by Ptolemy’s Geography. This is a list of place names and tribal names with their exact locations given in longitude and latitude. It was compiled by Ptolemy who was a Graeco-Roman living in Alexandria, Egypt, during the 2nd century AD. From the information given in the list it is possible to reconstruct of map of Ireland that appears strikingly familiar (see below). Indeed, a number of the names on the list are still easily recognisable (especially the rivers). Buvinda, is the Boyne, Senos is the Shannon, Logia is the Lagan, Obboca is the Avoca river (or possibly the Liffey), while Limnos may be Lambey island. It has also been suggested that the northern Regia shown on the map might represent Clogher hillfort, while Raeba may be the royal site of Cruchain, and Ivernis could be Cashel.

More information about Ireland can be found in the 1st century AD writings of Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian. He described Ireland as ‘a small country in comparison with Britain, but larger than the islands of the Mediterranean. In soil and climate, and in the character and civilisation of its inhabitants, it is much like Britain’. He goes on to state that he often heard his father in law the general Agricola ‘say that Ireland could be reduced and held by a single legion with a fair force of auxiliaries’ (see Waddle 1998, 374).

This assertion by Agricola and the possibility of a Roman invasion has been much debated. Dr Richard Warner, formerly of the Ulster Museum, has postulated that a large force of Romans/Romanised Britons may have invaded Ireland in the 1st century AD, probably through the southeast. He based this theory on number of factors, including a scatter of 1st and 2nd century Roman finds from Ireland and the similarity of some tribal names seen on Ptolemy’s map and those known from Britain and Gaul. He also speculated that a myth concerning an Irish Prince who returned from Britain with an army to seize power may have been based on reality. Could this be the same prince that Tacitus refers to when he states that Agricola welcomed ‘an exiled Irish prince in the hope of one day making use of him’? Although this is a very interesting theory, it remains unproven.

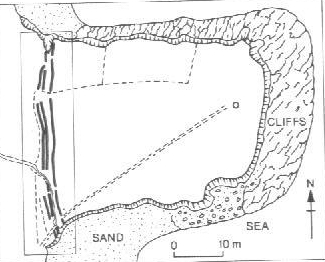

In the context of a possible Roman invasion one site has caused considerable controversy. This is a large coastal promontory fort at Drumanagh in north Co. Dublin. The fort occupies an area of circa 40 acres in size and is defended by three large ditches that cut off the landward approaches to the peninsula. The remainder of the site being protected by high sea cliffs. It has produced a number of artefacts of Roman origin, all of which, were found during illegal metal detecting (no archaeological excavations have been carried out at the site). These included coins dating to the reigns of Titus (AD 74-81), Trajan (AD 98-117) and Hadrian (AD 117-138), as well as Roman brooches and copper ingots (see Slayman 1996). These finds and the defensive nature of the site led some commentators to suggest that Drumanagh may represent the remains of a Roman fort. This view caused much debate and was challenged by a number of archaeologist and historians. The counter arguments were led by Professor Barry Raftery who suggested that Drumanagh was unlikely to have been a Roman military encampment but instead a local trading station linking Ireland and Roman Britain (in Slaymen 1996). It was probably populated by a mixture of Irish, Romano-British, Gallo-Roman, and others, doubtless including a few genuine Romans as well (Raftery 1996, 19).

Trade was certainly being carried out between the two islands during the Roman period as Tacitus states that Ireland’s ‘approaches and harbours are known from merchants who trade there’. It is likely that the Irish exchanged items such foodstuffs, woollen garments, hides, slaves and even wolfhounds. Evidence for the latter is seen in a 4th century AD reference to ‘seven Irish dogs, which so astonished Rome that it was thought they must have been brought in cages’.

In reverse, a wide range of material from the Roman world could have been traded with the Irish, and this may explain some of the Roman artefacts found in the country. This assemblage includes objects such as sherds of Samian and Arretine pottery from a number of native settlements, a Bronze ladle from Bohereen, Co. Meath, a small handbell from Kishawanny, Co. Kildare and at least 16 reliably documented finds of Roman coins (Bateson 1973). The latter includes isolated copper coins from places such as Freestone hill, Co. Kilkenny, gold coins from Newgrange and a number of very large hoards from Northern Ireland. For example, a hoard of 1500 silver coins as well as silver plate and ingots was found at Ballinrees, in Co. Derry. This early 5th century hoard may represent plunder stolen during Irish raids on the then disintegrating Roman colony in Britain or possibly monies earned by returning mercenary forces. Similarly, a hoard from Balline in Co. Limerick, which contained fragments of hacked silver plates and ingots, may represent captured loot.

In contrast, a collection of high status artefacts found at Newgrange, in Co. Meath appears to represent more ritualised deposition. These objects included gold coins, silver rings and sun brooches, which were buried in front of the great passage tomb. It is possibly that these were votive offerings which were deposited by merchants, travellers or even pilgrims from the Roman world. Additional evidence for ritual activity can also be seen at Randalstown, Co. Meath, where a Roman type brooch was recovered from the waters of a holy well.

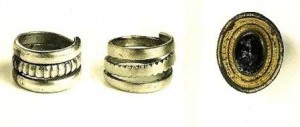

A small number of cemetery sites from Ireland have also produced Roman material. These include a series of burials, which were uncovered at Bray Head, Co. Wicklow in 1835. Although poorly documented these burials appear to have been extended skeletons with stones placed at their head and feet. The interments were also accompanied by copper coins of Tragan (97-117 AD) and Hadrian (117-138 AD). It is possible that this is evidence for the Roman burial custom of placing coins on the mouths and eyes of the deceased. These were intended as payment for the ferryman Charon so the river Acheron could be crossed into the land of the dead. Another set of burials was also found on Lambay Island off the north Dublin coast in 1927. Again poorly recorded these consisted of a number of crouched skeletons that were accompanied by a range of grave goods. The grave goods included Romano-British brooches of 1st and 2nd century date, an iron sword, bronze scabbard mounts, a bronze finger ring, an iron mirror and a beaded collar/torc. The torc is a well known North British type and suggests that the people buried at Lambay, if not from Romanised Britain, had very close contacts with it. It may be significant that the burials from Lambay and Bray are broadly similar in date to the apparent occupation of Drumanagh promontory fort (albeit the later is based on uncontexted coins). All three sites are located relatively close together and if nothing else are indicative of this areas close ties with Roman Britain, which after all, was just short sea voyage to the east.

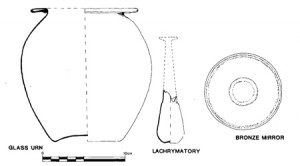

Outside of the greater Dublin region another apparently Roman burial was uncovered at Stoneyford, Co. Kilkenny. This was different to the burials already described as it consisted of cremated remains, which had been placed within a glass urn. The burial was accompanied by a glass phial possibly for cosmetics and a bronze mirror. This sort of burial was typical of the Roman middle class in the 1st century AD and suggests the presence of a Roman individual possibly woman, or even a Roman community in the King’s river valley, a tributary of the River Nore, just west of Thomastown (Waddle 1998, 375).

The question of whether the Roman’s invaded Ireland remains unanswered, although the current archaeological evidence would suggest that there were no large scale military incursions. For example, sites normally associated with the Roman military in Britain, such as large square/rectangular forts and linear, well-made roads, are conspicuously absent from the Irish archaeological record. It does seem, however, that there were extensive trade contacts between Ireland and Britain and it is likely that Romanised Britons and indeed Romans themselves would have been regular visitors to Irish shores. They probably came to trade, make political alliances, and to visit sacred sites such as Newgrange. Some may even have stayed long enough to form small communities, who chose to bury their dead according to Roman custom. Indeed, one of these immigrants was have to a profound effect on Irish history. After all, St. Parick, the patron saint of Ireland and the bringer of Christianity to the island, was a Roman Briton.

by Colm Moriarty

Further Reading

Bateson, D. 1973, ‘Roman material from Ireland: a reconsideration’, in Proc. Royal Irish Academy, 73C, 21-97.

Raftery, B. 1994 Pagan Celtic Ireland: the enigma of the Irish Iron Age. Dublin.

Raftery B. 1996 ‘Drumanagh and Roman Ireland’ in Archaeology Ireland,Spring Issue. p. 17-19.

Slaymen, S. L. 1996 ‘Romans in Ireland’ in Archaeology Magazine, Vol. 49, No. 3

Waddell, J. 1998 The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, wordwell, Dublin

Warner, R. 1996 ‘Yes the Romans did invade Ireland; And we don’t need Roman forts to prove it’, in British Archaeology, No. 14.

I thought everyone might like to know that the Discovery Programme’s latest research project has been designed to fully investigate the role Roman cultural influence played within the Later Iron Age in Ireland. The project has been designed to critically assess existing knowledge and to offer a new narrative for this formative period in early Irish history. Details about the aims and objectives of the project can be found under the Late Iron Age and ‘Roman’ Ireland (LIARI) project area at the website discoveryprogramme.ie. If anyone would like to discuss the topic in more detail with members of the LIARI project team please feel free to email us through the contacts section on the DP website or if you want to chat about any aspect of our investigations, post a topic for debate on our forum.

Jacqueline Cahill Wilson, Principal Investigator for LIARI Project

The Discovery Programme

63 Merrion Square

Dublin 2

i would like some more info on this please thank you

Pat Close-Happy New year.

Salve Jacqueline,

I’ve done quite a bit of research on this myself. I would love to have a chat with you about your findings. I have no problem sharing my research with you.

Vale,

Martin.

nerva@romanarmy.ie

Hi,

There are two small errors that occurred in your very interesting text – should be: “dating to the reigns of Titus (AD 74-81), Trajan (AD 98-117)”:)

With kind regards

Rafal

Thanks Rafal, I’ve corrected that now.

The well made, linear roads are actually not a hallmark of Rome at all. They were the hallmarks of the Celtic Druids. They built roads in perfectly straight lines along the lines of the equinoxes, which were wooden. Two survive, one in Kerry, one in Germany, but more have been located underneath Roman roads throughout Britain. They are about a metre below the Roman roads and predate them by 1000 years. The Romans were able to build straight roads because they built them right on top of the Celtic roads.

As far as Romans in Ireland, there are sure a lot of poems that tell of the Fianna fighting Daire Donn, the king of the world. They were in their prime at the time of these coins.

Great article, this stuff is fascinating, the true history of Europe is only beginning to be discovered.

You do know there are Romans in Ireland, right? Go to http://www.romanarmy.ie of FB https://www.facebook.com/groups/337802957619/?fref=ts

Thank you for this page. The link to the larger version of the old map of Ireland is not working.

I wonder, if there is any sign of the roman’s dividing of land, centuriation, in Ireland?

this is a very interesting topic in irish/roman history. i love archaeology and i want to be one of the people to excavate the Drumanagh site

Is there a good reason why the Drumanagh site hasn’t been archeologically explored?

Love the article, thanks for putting it together.