by Adrienne Corless

‘An archaeologist is really like a detective because he is always on the lookout for clues of various kinds which will help him in forming some idea of the way of life and customs of the people who lived in ancient times. As he is usually dealing with that period of time in which no written records were kept of the people’s activities, he has indeed a difficult task’. – Breandán Ó Ríordáin (from his personal collection of writings, 1956)

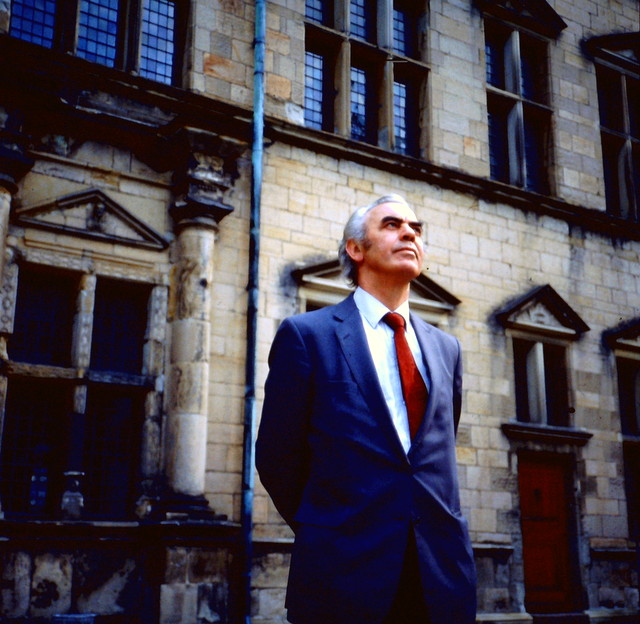

The name and work legacy of a man named Breandán Ó Ríordáin had lain before me every single day for eight years in my job at the National Museum of Ireland. A substantial section of the enormous archive of that museum’s Viking Wood Quay project (the Dublin Excavations Project), that I was charged with co-ordinating and researching, was the result of his handiwork. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, he had been one of the first-ever archaeologists to lead excavations in the deep, impressively-preserved Viking strata beneath Dublin city centre, in a project that still ranks among the most extensive urban archaeological excavations ever carried out in Europe. Save for a formal handshake and a quick pose for the official photographer at a formal museum function, I had never properly met him.

After my contract at the museum concluded in 2012 and I parted company with an archive of thousands of individual items like site plans, photographs and notebooks, and artefacts and ecofacts numbering in the hundreds of thousands, I made it a goal to finally get in touch with the man whose name was peppered over much of it.

Well over a year after I handed back my museum office keys, I wrote to him. He wrote back. I immediately recognised his handwriting on the envelope from the archive I had worked so closely with. He said that he’d be delighted to meet.

One grey November day, I took my maiden journey as a fully-licensed driver from Wexford to Ballymore Eustace, county Kildare, to wait for my date by the fireside at the delightful Ballymore Inn. He insisted on buying me lunch, and I spent a highly entertaining three hours in the company of a most pleasant gentleman who modestly and unassumingly shared with me the details of a fascinating life.

Early Life

I had known that Breandán came from county Galway – like myself – but wasn’t aware that his homeplace had been Tawin island. A tiny island off the coast of Oranmore, it is reachable by a long causeway and a bridge. Some time after that day I met with Breandán, I detoured from a visit to Galway city one day to see it for myself. A wide open flat land, roughly 0.5 by 1.5km, there were few houses, plenty of sheep, horses, children fishing for some form of sea animal off its rocky coastine. A quiet country road snaked along its length, and ended abruptly at the island’s old one-room school building, now a private residence, as the school closed its doors for the final time in 1992 and the last 13 pupils enrolled at Maree on the mainland instead. The school is where Breandán’s own father had been headmaster.

He was christened Antoine but better known as Breandán; academically he goes by A.B Ó Ríordáin, and, interestingly, he also wrote archaeological newspaper articles under various pen-names. He lived in the island’s schoolhouse with his family – his father Domhnall Ó Ríordáin, his mother Cáit (nee Búrca), his four brothers Colm, Seán, Gearóid and Domhnall, and his sisters Teresa and Caitlín. It was on the landing of this house that the young toddler Breandán would drink milk from a porter bottle, which he would chuck down the stairs when he needed a refill.

I learned that the island had once been a hotspot for speaking and learning the Irish language; Eamon De Valera had been director (1911-1913) of the Gaelic League summer school that was based on the island. A fluent Irish-speaker himself, Breandán’s father Domhnall had been associated with the same summer school and Breandán recalled that De Valera’s entire family had visited the island during summers.

Long before the commencement of a fascinating archaeological career, the child-Breandán had already had an intriguing exposure to Irish archaeology and the National Museum of Ireland itself; I was amazed to find that as a young boy, Breandán had already met with a National Museum of Ireland director, right in his own home – Dr Adolf Mahr (later accused of being a Nazi spy), had visited Tawin Island to meet with Breandán’s father, Domhnall Ó Ríordáin, regarding artefacts found in the area. In the 1930’s there had been a highly unusual spike in stone axe finds, all brought to the National Museum’s attention by none other than Breandán’s father Domhnall.

Domhnall Ó Ríordáin

Domhnall Ó Riordain, a fluent Irish-speaker writer born in Bellaghbehy, couty Limerick, was the principal of the island’s school and had a deep interest in history and archaeology. In his time, he was also an Irish language enthusiast, an author and editor; he was a member of the Gaelic League and a founding member of the Taibhdhearc Irish language-speaking theatre in Galway city. He also played the uileann pipes. He was interested in photography and developed his own photographs; this interest was evidently passed to Breandán, whose own images demonstrate a keen talent; photographs of site excavations at Viking Dublin between 1962 and 1975 were taken by Breandán and are archived at the National Museum of Ireland; Breandán also still keeps a personal collection of his own beautifully shot images of archaeology sites and excavation (some of which are used in this piece).

An abundance of stone axes at Oranmore and Maree

It seems that Domhnall Ó Ríordáin’s interest in archaeology had been a big influence not only on his young son Breandán, but on the entire district. Before sending a stone axe that he’d found locally to the National Museum, Domhnall took it to school to show to the schoolchildren. He certainly inspired the children, and by extension their parents and the wider community, who took themselves to the potato fields and beaches of the small county Galway parish to seek stone axes. They found them in such abundance that the National Museum keepers reduced the Finders Reward from 15 shillings to 5 shillings and even – to the chagrin of Domhnall Ó Ríordáin – returned axes to the senders in Oranmore! Researching an MLitt thesis on the topic of Mesolithic lithics, published 2006, Killian Driscoll notes that a third of all of county Galway’s stone axe finds came from the parish of Tawin-Maree, thanks in no small part to Domhnall O Ríordáin.

After his primary schooling, Breandán studied at the Jesuit College in Galway city. After rowing practice on the Corrib River, the brothers would cycle home to Tawin Island and do their homework before facing into the 40km roundtrip again the following day. Years later Breandán found himself settled in Wicklow’s Blessington next to the new man-made lake, just in time for the foundation of its rowing club, with which he was involved for many years.

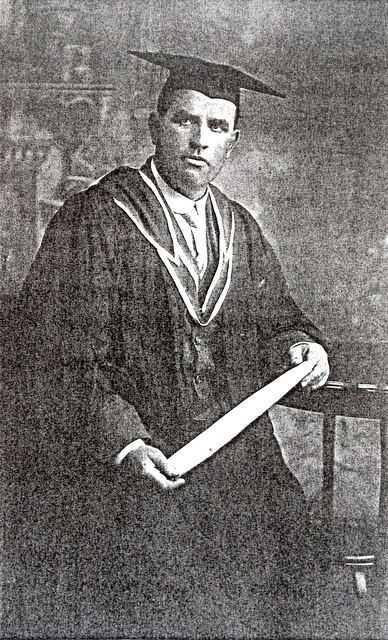

In 1945, when Breandán commenced third level education, he had the distinction of becoming University College Galway’s (now National University of Ireland, Galway) first full-time student of Archaeology (in which department I would enrol, more than fifty years later). As part of his time there he established the UCG Archaeological Society, and encouraged students from other disciplines to join.

Archaeological Excavation

“The Archaeologist uses light tools such as trowels, knives and small handpicks and with those the clay and stones are gradually removed – layer by layer. Small brushes are also used to sweep each layer of soil before removing the next layer. Notes and drawings as well as photographs are taken of everything discovered. In this way the archaeologist – through his careful work of excavation – can hope to build up a picture of the past”- Breandán Ó Ríordáin, 1956 (from his personal collection of writings).

It is easy to imagine that Breandán’s early encounter with a National Museum director had a significant impact, as he was to go on to take a role as Assistant Keeper at the National Museum of Ireland’s Irish Antiquities division. There, he met his lifelong friend Etienne Rynne who would later becoming Professor of Archaeology at University College Galway. Breandán remained happily focused on prehistoric topics at the museum, working on excavation investigations on behalf of the museum or analysing prehistoric artefacts, until one day in 1962 his boss, the then-director Joseph Raftery, dispatched him with a trowel to Dublin’s High Street.

There, he was expected to monitor the works of a JCB driver as the rubble of 18th century cellars was being cleared away, ahead of a proposed redevelopment of that neighbourhood by the Corporation of Dublin.

It was the start of everything Viking for Breandán.

“I was driven into it,” he smiled.

Under the rubble of 18th century cellars, a brown, soft, damp sediment was becoming evident beneath. This curious bog-like substance was not the result of a natural phenomenon – it was, in fact, the consolidated organic refuse of the earliest occupants of the town, and its accumulation had lead to unique conditions that preserved the ground-floor plans of the homes of the Viking Age inhabitants. In Viking and Medieval times, as Breandán himself wrote (‘Excavations in old Dublin’ 1984, p. 134), a great deal more material had come into the town – food, fodder, building stuffs and the raw materials for craftworking – than ever left it in the form of waste products. Discarded, disused, lost or forgotten possessions and floor surfacings engendered their own system of self-preservation as they close-quartered to create a tightly anaerobic environment, where even organic objects like wood, leather and textiles could survive time.

And so, just as the Vikings happened themselves dramatically on the Irish scene in the ninth and tenth centuries, through their rich and extensive material remains they announced themselves rather spectacularly once more in the Dublin of 1962. First, said Breandán, a beautiful antler comb turned up. Then more and more artefacts, of wood, leather, bone, glass, stone, silver, gold. A little trowel-scraping revealed the tops of astonishingly-preserved wooden buildings in the soil. Whole house-floor-plans, pathways and fences came to light.

The extent of survival was astounding.

A handful of enthusiastic archaeology students came to help. Breandán told them to take out their trowels and to “start scraping”.

Soon men from the Labour Exchange were drafted in and taught how to use trowels, knives, and brushes to carefully extract the evidence, while Breandán and his academic staff faced down the challenge of putting the relatively new techniques of archaeological excavation into play on a scale hitherto unknown in Ireland. They laid out site grids and painstakingly noted everything discovered and its findplace in hardback notebooks, made detailed survey plans and took multiple photographs.

Video link illustrating the archaeological excavations carried out by Breandáin O’Ríordáin.

Later in the 1960’s, a subsequent excavation site opened up at High Street, resulting in another enormous footprint of Viking inhabitancy, and after that, another at Christchurch Place, Winetavern Street, and in the 1970’s, Fishamble Street. Breandán and his team continued investigations over several seasons over the course of more than ten years, resulting in an enormous and meticulously neat and detailed archive of site notebooks, drawings, photographs, artefacts, ecofacts and samples of the preserved house remains and even of the very soil that preserved it all, all of which resides to this day at the National Museum of Ireland as part of the single dedicated section called the “Dublin Excavations”, the focus of my own tenure at the museum until 2012.

Breandán became director of the National Museum in 1979; by that time, another member of staff, then-Assistant Keeper Patrick Wallace, took over as excavations director on the Dublin investigations. When Breandán retired in 1988, he returned to his love of excavation, to being at the coalface of finding archaeology, to about being out of doors, onsite; very shortly after he cleared out his desk at the museum, a chance meeting with archaeological consultancy company owner Valerie J Keeley resulted in a new job monitoring new investigations. He continued to oversee excavation work throughout the eastern half of the country, right up until 2004.

The 87-year-old Breandán is remarkably fit and in good health, having recovered well from a stroke in January 2013. He and his wife keep a lovely garden, overlooking the lake at their Blessington home where they raised their family of four children, Mary, Aoife, Fiachra and MacDara. He walks often, meets his children and grandchildren regularly, and remains involved with local history; the very evening before our lunch date, he launched the Journal of Blessington-Lakeside Heritage Group in which he himself featured a small piece about the castles at Threecastles and Burgage; he refused to let me return to Wexford without a visit to the local bookshop in Blessington to purchase a copy for me, which he signed. Breandán still keeps all his early archaeology writings in a neatly bound red book, and has an extensive personal photography collection of Irish archaeological sites.

“Why did you want to be an archaeologist?” I asked him by the fireside that day in the Ballymore Eustace Inn.

He put down his fork and raised an eyebrow.

“Scraping the ground” was the reply, as though it were the most obvious thing in the world.

Enormously modest about his work legacy in the meticulously collected archive of Viking material in Dublin, Breandán knows he has had the kind of field and academic experience that any archaeologist would envy. It was clear to me – from his early days of seeking stone axes on a Galway coastline; to his enthusiastic and meticulous approach to record-keeping and evidence-retrieval on the most complex urban archaeological excavations the country had ever seen, at a time when modern archaeological excavation methods were only just being established; to his dedication to being onsite, with a JCB and a trowel, even post-retirement – that the prospecting was just as relevant to him as the actual finding; the journey so much as the destination; the ever-potential thrill of that moment of discovery that is the privilege of the archaeologist.

by Adrienne Corless

FURTHER READING

National Museum of Ireland, 1973. Viking and Medieval Dublin. National Museum of Ireland Excavations, 1962-1973. Catalogue of Exhibition. Dublin.

Ó Ríordáin, A.B 1969a Introduction. In C. Halliday The Scandinavian kingdom of Dublin, v-ix. Shannon. Irish University Press.

Ó Ríordáin, A.B. 1971 Excavations at High Street and Winetavern Street, Dublin. Medieval Archaeology 15

Ó Ríordáin, A.B. 1976 The High Street Excavations. In B. Almquist and D Greene (eds), Proceedings of the Seventh Viking Congress. Dublin. Royal Irish Academy/Viking Society for Northern Research

Ó Ríordáin, A.B. 1984 ‘Excavations in old Dublin’, in J. Bradley (ed.) Viking Dublin Exposed – the Wood Quay Saga. Dublin.

O Floinn, R and Wallace, P. 1988. Dublin 1000; Discovery and Excavation of Dublin, 1842-1981. National Museum of Ireland. Dublin.

This was a fascinating essay. I appreciate your sharing it.

Thank you very much for that mini biography, most interesting and informative. When I was not much more than a child in 1957 Breandán and a team of local people were excavating a burial site at Gortnacargy, in County Cavan. Later Breandán was a fairly regular guest at my parents’ home when he was in the area or passing through.

That was fantastic Adrienne – I know Brendán a long time and he is an absolute gentleman, – and a very good archaeologist (not that I am claiming to be in a position to judge) -that was fascinating ! He was the father of Viking archaeology in Dublin and many of his team passed onto Wood Quay, taught the younger generation, who then taught us !! As director of the museum he never really got the chance to do what you did, actually do post-ex which was an awful pity because I would imagine, from the publications he did do, a final report would have been brilliant.

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/tributes-paid-to-former-director-of-national-museum-of-ireland-1.3073381?mode=amp

Lovely to see such nice comments about our uncle. Sadly passed away yesterday. Sympathy to his wife Eilish, family and friends/former colleagues

Thanks Adrienne, that is a great article and all the more poignant given that Breandán has passed away and was buried yesterday. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam