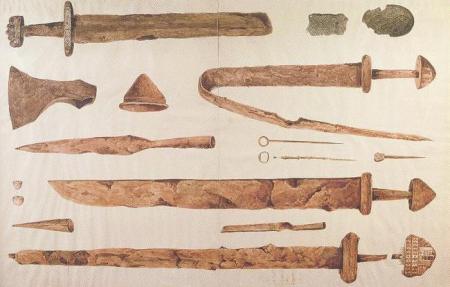

Recent research carried out by a number of archaeologists, especially Linzi Simpson, Dr Stephen Harrison and Raghnall Ó Floinn, has uncovered substantial evidence for early Viking warrior burials in and around Dublin city. The majority of these burials have been dated to the 9th century AD, a period when Dublin was home to a large Viking longphort. A longphort is essentially a defended base used to raid the surrounding countryside, beside which Viking fleets could be moored. The name is derived from the Irish words for ship (long) and bank/embankment (phort). The Dublin longphort was founded in AD 841 and it soon became the epicentre of Viking activity in Ireland. Large numbers of warriors passed through its gates in search of wealth and riches through force of arms. However, as the archaeological evidence now indicates, the only reward many received was a shallow grave. As pagan warriors, these casualties of the Irish campaigns were typically buried with militaristic grave goods, such as swords, spears, shields and daggers, for use in the afterlife. This marks them apart from contemporary Irish burials which respected Christian conventions and were carried out without grave goods.

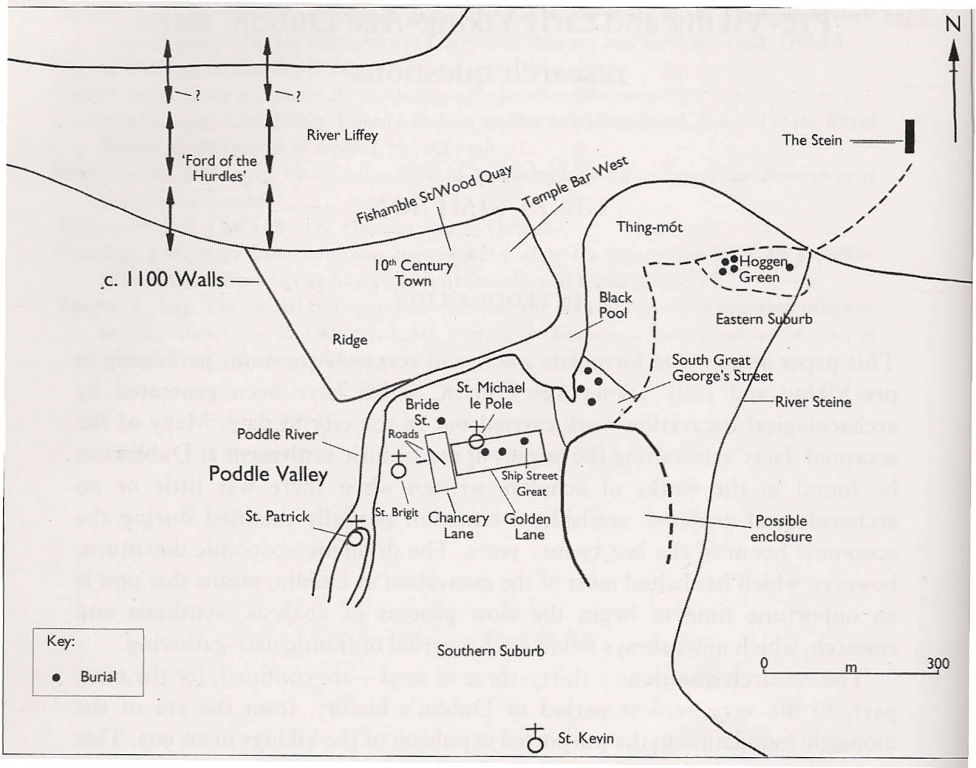

Although the majority of burials were uncovered during the 18th and 19th centuries, a number of recent excavations have revealed further Viking remains. These ‘modern’ burials, with the exception of two outliers at Kilmainham and Finglas, have all been identified along the Poddle valley, which is located in the southern part of the modern city centre, to the south of Dublin Castle. The Poddle was an important tributary of the river Liffey and it defined the southern and eastern sides of the Viking walled town. It has now been completely culverted (covered over), but its outflow into the Liffey can still be seen just beside the Millennium footbridge (just to the west in the south quay wall). Nearly all of the burials were of young men, who were interred with weapons, suggesting that they were the remains of warriors.

The first of these Viking burials was uncovered by Linzi Simpson at Ship Street Little in 2001 (Simpson 2005). It consisted of the truncated skeleton of a young male who was aged between 25 and 29 at death. He had been buried in shallow grave that also contained a pattern welded sword and number of small personal items (rings and beads). Radiocarbon analysis indicated that he had died circa 665-865 AD (2 sigma). The same archaeologist was to uncover four more Viking burials at South Great Georges Street in 2003 (behind the Long Hall pub) (ibid). These represented the remains of four young males aged between 17 and 29, who had been interred with a variety of grave goods including knives, shield bosses, combs and decorated pins. The remains were situated around the edge of the original dubh linn or ‘black pool’, from which the present city got its name. Radiocarbon analysis indicated that three of the burials dated from circa AD 670-882 while the fourth was slightly later in date at circa AD 786-955. Isotope analysis was also carried out on the burials and this suggested that two of the dead warriors came from Scandinavia, while the remaining two were probably from the Norse colonies in the Northern or Western Isles of Scotland.

A short distance to the west, at Golden Lane, Edmond O’Donovan indentified a further two Viking burials in 2005 (O’Donovan 2008). These were situated just outside an early medieval cemetery associated with the church of St. Michael le Pole, from which 268 skeletons were also recovered. Interestingly one of the Viking burials at Golden Lane was that of an elderly female, while the other consisted of young male (c.20-30 years old). The female burial was accompanied by decorated bone buckle, while the male burial contained a spear-head, a knife, a belt buckle and two lead weights. The radiocarbon dates for these burials ranged between AD 688-870, which is remarkably similar to those from Georges Street and Ship Street.

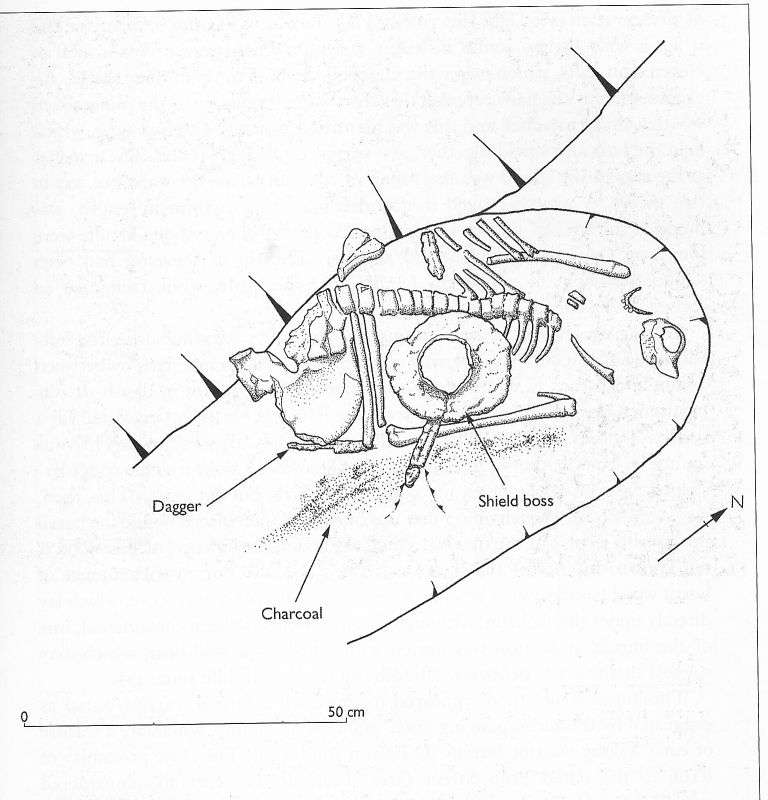

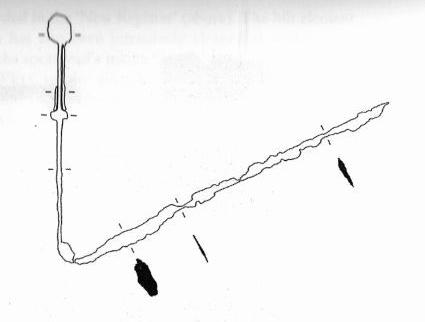

To these newly uncovered Viking burials along the Poddle valley can be added a much earlier discovery at Bride Street, which is just a short distance to the west of Golden Lane. This burial was unearthed beneath the street surface during drainage works carried out in 1860. It was accompanied by a sword, a spear-head and a shield boss, suggesting it was the remains of an important warrior. In this instance the sword had been bent before burial in an act of ritual decommissioning, while the shield boss had also been damaged (Harrison 2010). Interestingly a Bronze Age halberd, which was also bent, was recovered during these Bride Street drainage works. This is the only recorded Irish halberd that is bent, which has led Dr Stephen Harrison to suggest that it may have originally formed part of Viking burial’s grave goods (ibid, 146). A case of an antiquarian Viking?

Not far to the east of the Poddle valley burials another Viking cemetery was located in the Suffolk Street/College Green area. This area was referred to as Hoggen Green in the early literature, with Hoggen being derived from The Norse word ‘haugr’ meaning burial mound. At least two of these mounds survived into the 17th century when they were demolished. One of the mounds is recorded as having a very elaborate cist burial. Further Viking graves were recorded at this location in the 19th century, with a number of grave goods being recovered including two swords, four spearheads and a shield fragment. Much further west in the Kilmainham and Islandbridge area another, exceptionally large cemetery was uncovered during railway building in the 19th century. It contained at least 35 individuals, who were primarily males of fighting age who had been interred with swords, shields and spears, as well as items associated with trade such as weights and balances. The recovery of such an extensive cemetery to the west of the present city has led some archaeologists and historians to suggest that there may have been a second longphort at this location, possibly where the Camac River meets the Liffey. To these large cemetery sites can be added a number of additional Viking burials that were recorded in the 18th and 19th centuries. These include a female skeleton from the Phoenix Park and probable warrior burials from Kildare Street, Cork Street, Parnell Square, Mountjoy Square, and slightly further afield at Donneybrook and Dollymount.

What is remarkable about these Viking burials is their sheer number. Dublin accounts for nearly half of the Viking burials with weapons identified in the British Isles, which is an extraordinary figure (Harrison 2007, 43, Simpson 2010, 63). This number of dead young men must be a proportional reflection of the huge amounts of Viking adventurers coming to Ireland during this period, something which is complemented in the annals casualty-lists for numerous contemporary battles (Simpson 2010, 63).

by Colm Moriarty

Related posts on Vikings

Bones of the Vikings when raiding goes wrong

Further reading

Harrison, S.H. 2010 Bride Street revisited-Viking burial in Dublin and beyond. In S. Duffy (ed.) Medieval Dublin X. Dublin, 126-152 Simpson, L. 2010 Pre-Viking and early Viking Age Dublin: some research questions. In S. Duffy (ed.) Medieval Dublin X. Dublin, 49-92.

Simpson, L. 2005 Viking warrior burials in Dublin: Is this the Longphort? In S. Duffy (ed.) Medieval Dublin VI. Dublin, 11-62.

Simpson, L. 2010 Pre-Viking and early Viking Age Dublin: some research questions. In S. Duffy (ed.) Medieval Dublin X. Dublin, 49-92.

O’Donovan, E. 2008 The Irish, the Vikings, and the English: new archaeological evidence from Excavations at golden Lane, Dublin. In S. Duffy (ed.) Medieval Dublin VIII. Dublin, 36-130.

O’Brien, E. 1998 A reconsideration of the location and context of Viking burials at Kilmainham/Islandbridge, Dublin. In Manning (ed.), Dublin beyond the Pale: Studies in honour of Paddy Healy. Wicklow, 35-44.

O’Floinn, R. 1998, The archaeology of Early Viking age in Ireland. In H. Clarke, M. Ni Mhaonaigh and R. O’Floinn (eds), Ireland and Scandinavia in the Early Viking Age, Dublin 132-165.

“Dublin accounts for nearly half of the Viking burials with weapons identified in the British Isles, which is an extraordinary figure”

Even more extraordinary seeing that Dublin is in Ireland and not in the ‘British Isles’ Sad to see an excellent article containing such a glaring factual error

The island of Ireland is one of the British isles… It’s just that the Republic isn’t part of Great Britain or the United Kingdom! Great article! 🙂

Sorry to be the bearer of bad news but Ireland is in the British Isles, maybe you should check this out with a Geography teacher !

Hi Martin,

The plain fact is that the island of Ireland is part of the British Isles (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Isles). The only thing that is sad here is that you felt it necessary to besmirch an excellent, well-researched, engaging, and extremely informative blog post with your ill-informed prejudice.

Great blog post!

Hey guys,

Great article but may I just add, regarding the location of the burial ground further west from the city centre around Kilmainham/Islandbridge,

Is it not true that when the Normans took Dublin in 1169/70 the Viking population was banished out of Dublin to an area we know today as Oxmantown which actually translates to homestead of the Eastmen in Irish it translates to Scandinavian homestead.

Well my point is if you look at a map of Dublin you will see the burial site located in Kilmainham/Islandbridge is not at all far from Oxmantown, perhaps it was used by the residents of Oxmantown?

When Dublin was attacked by the Normans the Vikings would ofcourse had of sustained casualties, so when the Viking populace where banished they had the opportunity to bury their men folk at Kilmainham. .

These British islands are Unique, each one having its own people & History.

As an Englishman ! ? (Yorkshire Viking? & Staffordshire) who loves,& traveled through out Ireland for 48 years.

You have an amazement of Beautiful land & History!!!! From 5000 years,

Be Proud & wonder for a second who you are!!!.

Under the Interpretation Act 1978 of the United Kingdom, the legal term British Islands (as opposed to the geographical term British Isles) refers to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, together with the Crown dependencies: the Bailiwicks of Jersey and of Guernsey

Great article

Will visit the site

Hi, what is the significance of the lead weights among the grave goods? What was their purpose? Fishing?

Hi Pat, the used the lead weights in conjunction with a scales to weigh up the silver and gold they captured/stole. Objects such as jewellery, chalices etc were typically chopped up in to smaller pieces of ‘hack silver’, which could then be used as a form of currency. The weights allowed then to quickly ascertain how much each pile of hack-silver was worth.

Hi Colm, great article thank you! I’m just wondering if there is any literature on the grave at Kildare Street? I’d love to know where on the street it was found.

Hi Annie, thanks for your kind words 🙂 The identification of grave from Kildare Street is based on the discovery of sword (most likely from a burial) during the construction of the Dublin Museum of Science and Art (now the National Museum of Ireland) in 1885. The only record for the find is from an entry in the Science and Art Register for 1898. The sword now forms part of the National Museum’s collections and some more info on the discovery can be found in the publication ‘Viking Graves and Grave Good in Ireland’ by Stephen Harrison and Raghnall O Floinn. Hope this helps, Colm

That’s a great help Colm thank you!

Hello, Colm!

First off, wonderful article! It was extremely informative and has helped a lot with my own personal research on vikings in Ireland. I am curious to know if you know of any more information specifically surrounding the grave site at Finglas. Thank you!