I recently described how the forces of Brian Bóruma, king of Munster, attacked and destroyed a sacred grove of trees belonging to the Vikings of Dublin. This wood appears to have been associated with Thor, the Viking god of thunder, and its destruction by Brian Bóruma was probably an act imbued with both religious and political symbolism.

However, as the Irish Annals clearly show, the belief in sacred trees were not just confined to the Vikings of Dublin, but was also found in contemporary Gaelic society. Typically referred to as bile in the early texts these ‘sacred’ trees were often associated with Irish royal inauguration sites. They appear to have played an important part in Irish kingship ceremonies and as a result were sometimes targeted by rival dynasties.

Indeed, Brian Bóruma himself was to suffer this ignominy in 981 AD when the forces of Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Meath, swept into Munster. The Meath men journeyed straight to Maigh Adhair in modern Co. Clare, which was the inauguration site of Brian’s clan the Dál Cais. Here they deliberately targeted the sacred bile, cutting it down and digging up its roots[i]. Destroying this tree was undoubtedly a highly symbolic act and a direct affront to Brian’s kingship.

However, it appears that the men of Meath were not wholly successfully in their endeavours. Not alone did Brian’s kingship endure and prosper but the great tree at Maigh Adhair also survived[ii]. 70 years later it was still standing, but its days were now numbered. In 1051 Aedh O’Connor, King of Connacht, attacked Magh Adhair and once more the sacred bile was the focus of the assault. This time the attack appears have been more successful as the tree is described as being left ‘prostrate’ on the ground[iii].

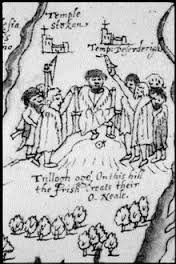

The annals also record other attacks on sacred trees. For example, in 1129 AD the sacred bile of the Ui Fiachra Aidhne kings of south Galway, the Ruadbeithech (red birch tree), was cut down. Similarly, in 1099 an army led by Domhnall Ua Lochlainn of the northern Uí Néill defeated the men of Ulster and afterwards cut down their sacred tree, which was known as ‘Craebh-Tulcha’[iv]. It was twelve years before the Ulster men could exact their revenge. In 1111 AD they sent a force deep into Uí Néill territory and attacked Tulach Óc, the inauguration site of the Uí Néill kings, where they cut down the sites sacred grove of trees[v]. They were to pay dearly for this insult, however, as in retaliation the Uí Néill raided Ulster, stealing over 3,000 cows in retribution.

As these incidents illustrate, sacred trees appear to have been powerful symbols of royal authority and as a result were often targeted for attack. Their exact role in kingship ceremonies remains uncertain but it may have been something to do with the slat na righe (rod of kingship). This was the principal ritual prop and archetypal symbol of legitimate royal authority[vi] and it may have been cut from the branches of the bile during inauguration ceremonies. This is suggested by the 12th century Life of Saint Máedóc, which records how the king of Breifne was anointed with a rod that had been cut from the sacred hazel tree of Saint Máedóc[vii]. Although this latter account is an overtly Christian one, it seems likely that the use of sacred trees/bile in kingship ceremonies had its origins in older, pagan beliefs.

[i] Annals of the Four Masters, M981.8. Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed 20-08-13

[ii] or possibly was replaced with a new tree

[iii] Annals of the Four Masters, M1051.13. Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed 20-08-13

[iv] Annals of the Four Masters, M1099.7. Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed 20-08-13

[v] Annals of Ulster, M1111.6. Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed 20-08-13

[vi] FitzPatrick, E, 2004 Royal Inauguration in Gaelic Ireland C. 1100-1600: A Cultural Landscape Study, Boydell Press, p. 58

Thanks for this wonderful entry, Colm. It spares me a great deal of work 😉 as I promised my readers to do a similar entry… So, a link to that will be in my blog.

Thanks Mujerárbol! It was inspired by your question after the Thor’s Wood post 🙂

What kind of tree?

Hi Patricia, the sources don’t really mention the tree species with the exception of St. Maedoc’s sacred tree which was a hazel. Colm

So the tradition of the sacred tree or sacred grove was still going in 1051 AD and 1111 AD? This seems remarkable and suggests that the pre Christian religion remained in place much longer than the arrival of St. Patrick.

I will need to do more reading to get a handle on when the old religion and traditions really disappeared. I guess I”ve always imagined that once St. Patrick arrived, it quickly switched over, but as I consider it, that is very unlikely, especially when I consider the power of kings.

All in all, I’d love to read more about ancient traditions that kept going long after the arrival of Christianity in Ireland.

never, they are all still with us in one form or another

I think we have to be careful in how we interpret sacredness in the period. Just because there practices in the 11th Century that seem unrelated to Christianity doesn’t mean they predate Christianity.

Bob I think you should read “The White Goddess” from Robert Graves. Also, remember, Celts were venerating groves, particularly Oak groves, Bards were using Beech tree bark to write their poems on it (many were burned by early Christian ((Belissama ou l’Occultisme Celtique by Ernest Bosc) and even Christian writers who published Celtic based stories (such as Chretien de Troyes and Von Eschenbach mentionned sacred trees. Now remember those writers were Benedictine monks and Saint Bernard himself said “you will learn more from trees in the forest than in all of your books)

When it comes to reading about those times, we are very reliant on monks like Tireacháin and Muirichú, who compiled their versions over 200 years after the ‘alleged’ events. These venerable gentlemen were operating under an agenda which, in hindsight, was biased and prejudiced to their organisation. A valuable insight may be that Patricus was never mentioned in any of the writings of his contemporaries. If he was such a huge influence on his times, why would they ignore him? Could it be that the version we have been subjected to, is not entirely true?

As regards the trees identities, hazel would be a major contender as it was a very great source of nutrition, year on year, and was a major mainstay in the diet of the day. Many trees that were held in reverence would usually refer to the usefulness of its properties.

The so called ‘old religion is alive and well and sacred trees are still an important facet. Blessed Be.

interesting that it even spread to Seagrove in the USA, as the 2nd picture is from there….

http://studiotouya.blogspot.com/2009/06/oak-tree-fall-down.html

My family is named after the holly tree (Cuillieann). And even when anglicized to Collins still represents hazel. They can take our history but they really cant now can they;)

A Facebook friend who lives at Waterford posted a photo of a highway weaving around a small tree & bush due to the legend that the fairys live there. This is in the 21st century.