‘Bitter is the wind tonight

It tosses the ocean’s white hair

Tonight I fear not the fierce warriors of Norway

Coursing on the Irish sea‘

(A translation by Kuno Meyer)

This anonymous poem is written in the margins of an Early Irish manuscript that now resides in the monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland. Most likely dating from around 850 AD, the text may have been complied in a northern Irish monastery such as Nendrum or Bangor (both in Co. Down).

In a just a few, short words it conveys the sense of dread that was permeating through Irish monastic communities in the 9th century AD. During this period Viking raids were an every present danger and the Irish Annal’s record numerous attacks on monasteries. In such a climate of fear and uncertainty, it is not difficult to understand why a monk would wish for stormy seas and a respite from ship borne assaults.

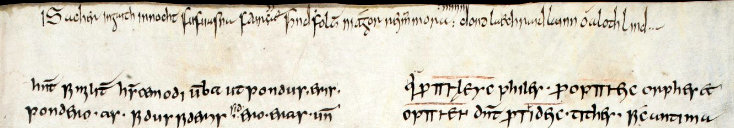

‘Is acher ingáith innocht .

fufuasna faircggae findḟolt

ni ágor réimm mora minn

dondláechraid lainn oua lothlind’

The original Irish text of the poem.

Sources

St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 904: Prisciani grammatica (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0904)

.

Brilliant! I have never before seen the original version. Interesting how it ended up in St Gallen. You could hardly get further from the Vikings than Switzerland!

Keep in mind that St. Gallen was founded by Irishmen. Gallus himself was Irish-born, and came to the continent with Saint Columbanus and eleven others in around 589. They settled in Luxeuil and founded an abbey there before being forced out in 610. They made for Bregenz, but Gallus fell ill and remained in what’s now Switzerland/Swabia (Columbanus was none too pleased by this). So Gallus set up a little hermitage in the forests near Lake Constance, and lived out the rest of his life there.

For several hundred years thereafter, Irish and Anglo-Saxon monks alike came to work there. The fact that the abbey was one of the most respected ecclesiastical institutions in Europe in the 800s and 900s would have certainly made the trek from Eire and Alba all the way to Swabia more palatable!

This poem and translation show the true beauty of the Irish language. While the translation is accurate it is “leamh” – boring, plain, undramatic, whereas the original reeks of depth, feeling, onomatopea, rhythm, life, vibrance. Irish is the verbal equivalent of oil painting- malleable and so expressive k the right hands. I love it – it is an artist’s language.

Where do I see the Irish word for viking?

‘Lothlind’ is one of Irish words for the Viking’s homeland 🙂 Lochlannach being another name for a Viking

Chuidigh seo go mor liom. A great help. Helen Waddell, Latinist and author wrote how she almost lost the power of her legs when she came upon these old manuscripts whilst researching the mediaeval poetry of Europe. She had strong connections with Co. Down and had a great love for ‘ the Irishmen’, the monks who played no small part in saving the great Latin classics of Europe and contributed to them.